It’s funny the number of people who still judge works of art by the supposed technical skills required to produce them. “I could do that” is for those people the worst condemnation, in a world where the genius of a work of art is measured by its ability to depict things “realistically” (and therefore the difficulty one might have to reproduce it). At some point it might very well have been so, but the advent of photography rendered the sole ability to render a scene objectively relatively futile (impressionists were quick to realise this) as it is much more effective at faithfully reproducing its subject than painting.

Ironically, I doubt many people who reason like this would pay to come visit it if I were to put on a show exhibiting perfect reproductions I had painted of the Mona Lisa and Starry Night, for example. I don’t blame them. In his book The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1937), Walter Benjamin says: “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be…”. My Mona Lisa would have no relevance other than to show my ability to reproduce a painting.

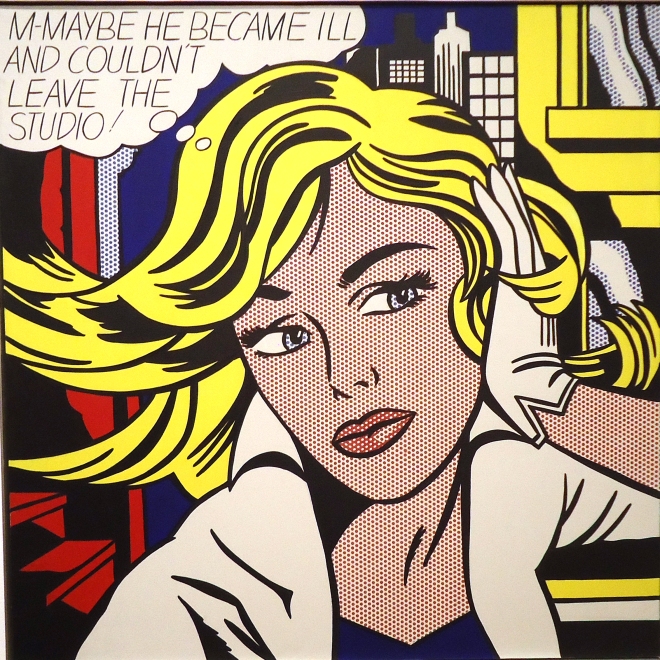

Context is a lot of what makes art art. In an older post, I’d briefly mentioned Roy Lichtenstein. I’ve seen comments being made about his paintings being a rip-off of the comic-book artists’ work they are drawn from. Although the fact painted reproductions of individual panels are now literally worth tens of millions seems obscene (especially as they were taken from a comic probably only sold for a few dollars), I disagree.

I like the definition of poetry given by Wikipedia very much: “poetry is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, the prosaic ostensible meaning”. I think that last part about adding or transforming the pre-existing meaning of something can be extrapolated to all other art forms. What’s important in Roy Lichtenstein’s work, for example, is not necessarily the image itself; it’s the idea behind it of transforming an otherwise mass-produced panel into a unique piece of art with a “unique presence in time and space” and what that says about consumerism.

Anything, (any object, drawing, action, footage, etc.) can be considered art depending on the context. The context is a lens through which something is viewed, and if that something evokes more through that lens than it would without it, it is art.

This doesn’t mean that all art is good, but next time you find yourself thinking that you “could do that”, think about what the piece’s context is and what it’s trying to say. Think also about if you actually did do it yourself: would it have any more meaning than the original?